Nativist Narratives Emerged from and Continue in Academia

By Stephen Oliver

In the aftermath of a bitter and divisive 18-month presidential campaign, Americans are trying to figure out how campaign rhetoric might translate to future policies for its residents, including those living along the country’s southern border.

Republican President-elect Donald Trump’s campaign slogans and statements were perhaps some of the most blistering and vicious in recent history, with particular virulence aimed at Hispanic immigrants. Within the first five minutes of the announcement of his candidacy, Trump perpetuated a negative narrative and stereotype of Mexican immigrants as a criminal and cultural threat to the nation when he stated, “They’re sending people that have lots of problems, and they’re bringing those problems with us. They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists. And some, I assume, are good people.”

How his discourse informs actual policy in a Trump administration remains unclear. Where it came from, however, has a long history not only in populist politics, but also in the country’s formal and informal institutions, including in the realm of education.

The battle between two diverging schools of thought on immigration and borders, and their corresponding narratives have been playing out in some the nation’s most esteemed universities and in local high schools for decades, if not for centuries.

Nativist rhetoric emerges from the halls of higher learning

With 17 U.S. universities ranked in the top 25 worldwide according to Times Higher Education, the nation’s higher education system is one of the best in the world. Despite the accolades, the country’s colleges and universities have a history of propagating and advocating for racist public policies, said Dr. Anna Ochoa O’Leary, Head of the Mexican American Studies Department at the University of Arizona. “We have institutional xenophobia in our immigration laws,” said O’Leary, which has been advanced by “so-called scientific facts to prove notions that white Americans are the superior race.”

“One of the difficulties we have with the intersection of academia and racism is that a lot of academia is rooted in a positivist interpretation of the world,” says Dr. Nolan Cabrera Associate Professor in the Center for the Study of Higher Education at the University of Arizona. “The numbers don’t lie. The problem is, in order to make sense of where your numbers come from, you need to create a narrative around it.”

A polarizing example of this comes from a 2009 graduate of Harvard's John F. Kennedy School of Government. Jason Richwine’s doctoral dissertation illustrates what O’Leary and Cabrera believe to be attempts to apply scientific study to race and immigration law.

In his dissertation, titled “IQ and Immigration Policy,” Richwine claims that Hispanics are less intelligent than “native whites,” and that genetics, in part, are to blame. He goes on to argue that:

“No one knows whether Hispanics will ever reach IQ parity with whites, but the prediction that new Hispanic immigrants will have low-IQ children and grandchildren is difficult to argue against. From the perspective of Americans alive today, the low average IQ of Hispanics is effectively permanent.”

Richwine has spent years defending his research against claims of being racially loaded pseudo-science, and in a National Review op-ed said that he has been mischaracterized as a racist by the media’s intent on “gotcha” journalism because he dared to take on a controversial topic. In an email interview, Richwine declined to answer specific questions about whether his research steered clear of racist assumptions stating that, “it would be re-litigating the dissertation controversy that I've already written plenty about.” He added, “I'll just reiterate that, contrary to many media reports, my dissertation explicitly rejects an immigration policy based on ethnicity.”

Looking to the future, however, Richwine is optimistic. When asked about any impact that a Trump presidency might have on further academic study of demography, psychometrics, and immigration he remarked, “I'm delighted that the new administration is going to take enforcement seriously and will hopefully look at changes to legal immigration policy as well. I hope this spurs lots of new research.”

“Look, you don’t have to throw the baby out with the bath water,” said Dr. Cabrera in response academic pursuits of dealing with race and ethnicity. “I like empiricism, I think it can serve an important function in our society in helping make informed decisions, but we need to be careful about the way that we talk about it because a lot of times people hide prejudice behind objective scientific fact, when in fact it is very subjective in its process.”

“Academia has made some very substantial strides,” adds Dr. Cabrera, “but it also has a lot of apologies to make for really damaging communities of color in the process.”

The nation’s relationship with borders, immigration and multiculturalism is complex and divisive. This past November, in California, voters put an end to an almost 20-year ban on bilingual education, while the President-elect campaigned and earned votes by stating, “We have a country, where, to assimilate, you have to speak English. I’m not the first one to say this.” Similar to the battles over science and race that are unfolding in our universities, narratives of immigration and multiculturalism in education are taking diverging paths across the country.

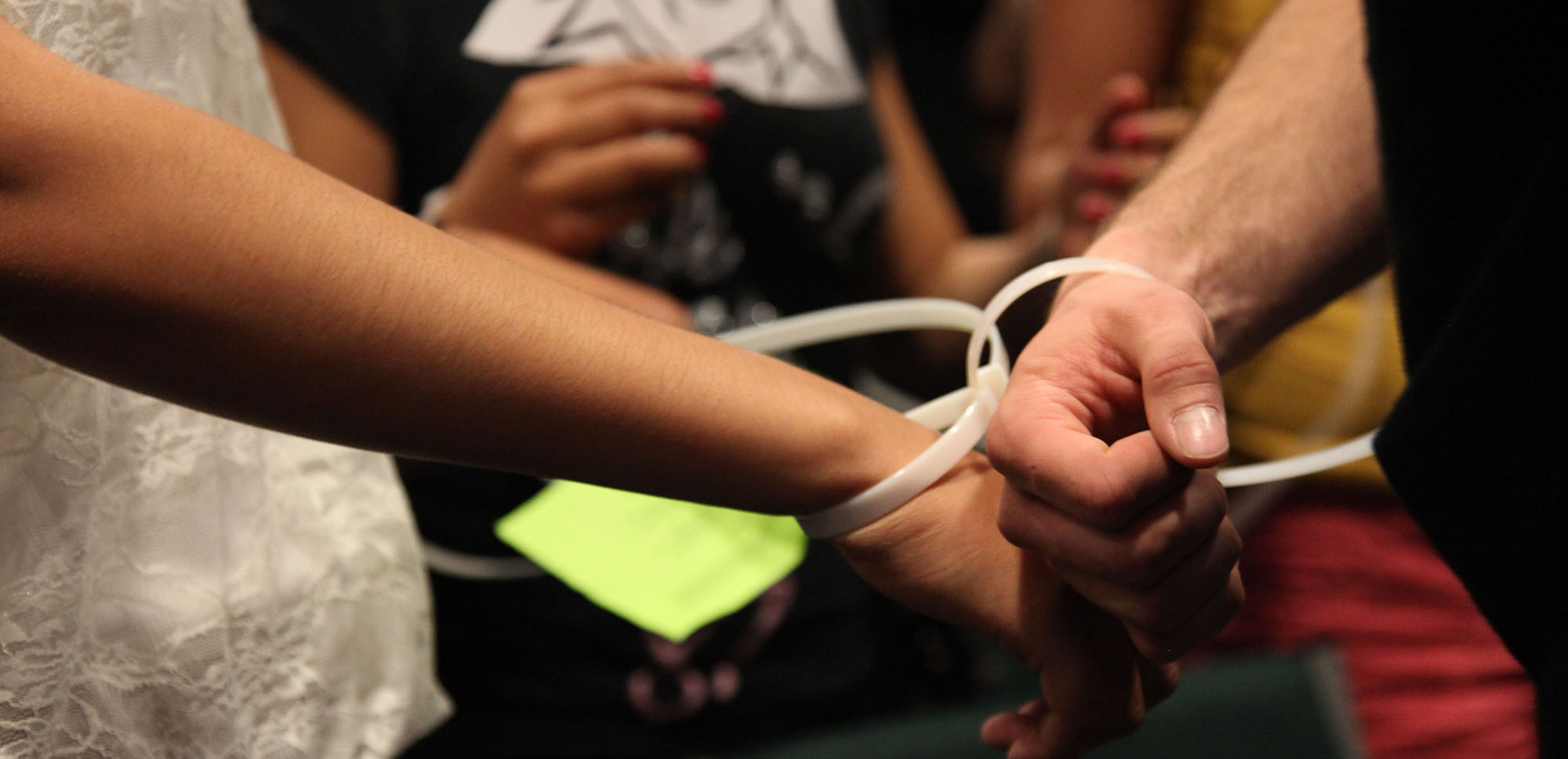

“I still feel like Curtis Acosta’s Chicano literature class is the reason I decided to go to college,” said Xavi Ramírez, a 2010 graduate of Tucson High and current graduate student in Latin American Studies at the University of Arizona. Photo credit: Stephen Oliver.

Academics and high schools counter a historically dominant narrative

In September, California Governor Jerry Brown signed into law a bill that requires all the state’s public high schools to adopt an ethnic studies curriculum by the 2019 school year. Many see this as a significant step to creating a more ethnically inclusive environment in schools and a way in which dominant narratives of Anglo-American history can be challenged.

Yet, the history of incorporating ethnic studies, particularly Mexican American studies, into school curricula has reflected the broader national debate on immigration and multiculturalism where progress has been met with resistance.

Six years ago, despite protests and public outcry, Arizona Governor Jan Brewer signed House Bill 2281 into law in May of 2010. The law, backed by conservative Republican and then State Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Horne, sought to ban programs that, among other things, “promote resentment toward a race or class of people.” In effect, the law led to the disbanding of a highly successful Mexican American Studies program at Tucson High School.

Laws like HB 2281 have a historical legacy. In 2008, while Richwine was nearing completion of his dissertation, another Ph.D. candidate at the University of Arizona provided evidence of another perspective. In her examination of Tucson Unified School District’s 20th century desegregation movement, Maritza De la Trinidad argued that “Discrimination in Arizona was partly due to its ‘southern’ character, which was evident in its school segregation laws… Separate educational facilities undoubtedly resulted in separate and unequal education.”

Discrimination in Arizona was partly due to its ‘southern’ character, which was evident in its school segregation laws… Separate educational facilities undoubtedly resulted in separate and unequal education.

In Arizona, even after the civil rights movements of the 1960s, the legacy of school segregation remained and Chicano history was largely ignored in public school curricula, which is why programs such as Mexican American Studies were created.

Maya Bernal, graduated from Tucson High School in 2008, after going through its Mexican American Studies program. “The class definitely helped me enjoy school, before I was pushing through, acquiescing with the mundaneness of what school does to you,” said Bernal.

“It gave you a sense of place, an academic identity, ” she said.

“Self-hate is a huge issue,” explained Bernal “and that’s what Raza Studies taught -

to not hate yourself, no matter where you come from, no matter who you are, no matter what skin color you’re born with…so it’s about knowing the history and the reality of where you come from.”

When asked if he ever felt like what he was being taught promoted racial resentment, Xavier Ramirez, a 2010 graduate of Tucson High and current graduate student in Latin American Studies at the University of Arizona, explained that every Chicano literature class began with the reciting of a poem adapted from a Mayan precept by Luis Valdez called In Lak’Ech. From memory, he can still recite the work in both English and Spanish, which states that through the love and respect for others one receives love and respect of one’s self.

“In reality all it is, is us learning a different perspective. How do you teach someone about slavery and have them not be pissed that people were owning other people? That doesn’t mean that we shouldn’t teach it,” Ramirez said.

Aside from students’ anecdotal successes, the program had a notable positive impact on students in terms of preventing dropouts: a 2012 study co-authored by Dr. Cabrera showed that students in program were 51% more likely to graduate than students of similar ethnic background who were not in the program. Since its disbanding, TUSD has created a so-called “culturally relevant” curriculum.

By dismantling Tucson High’s Mexican American Studies program, the state ended a program that challenged conventional ideas of Manifest Destiny, white supremacy, identity, and indigeneity. The now defunct program critiqued the same narratives that have appeared in Arizona politics for decades, in some of the most respected institutions such as Harvard University, and the very ones that Trump used on his path to the White House.

De la Trinidad, who is now an assistant professor of history at University of Texas-Rio Grande Valley is cautiously optimistic about the current turn in U.S. political circles and the implications this could have on Mexican American Studies programs across the country, “Ethnic studies emanated from the desires of students in the late 1960s and the movement has gone through various presidencies,” said Dr. De La Trinidad. “It’s like the stock market, it goes up and down. I’m optimistic that we’ll continue to push forward and continue to help students meet their potential.”