‘What do you mean, you don’t like my kind?’

A look into how residents of northern and southern border communities perceive immigrantsBrenna Bailey in Sweet Grass, Mont./Coutts, Alberta, and Nogales, Ariz./Nogales, Sonora

Cesar Leyva, a Mexican national who resided in the United States for 13 years on a 10-year tourist visa, was one of the 235,000 unauthorized immigrants removed by ICE authorities in 2015.

Leyva is a father to a U.S. citizen, entrepreneur and taxpayer. He provided for his entire family when he lived in Tucson, Ariz., and benefitted the community. Since he’s been deported, Leyva says his life has “frozen,” and his family dynamic has been effectively ruined, since he may never again be able to visit his son in the States.

He doesn’t understand why so many Americans, including President Donald Trump, label him and “his kind” as rapists and bad hombres — even in Arizona, a border state whose population is around 31 percent Hispanic.

“At one point I went to a Circle K and someone told me, ‘Oh, we don’t like your kind,’” Leyva says. “And I said, ‘What do you mean you don’t like my kind?’”

∙∙∙

While President Trump has promised to rid the United States of undocumented immigrants, the idea of mass-deportation isn’t new. Some activists dubbed President Barack Obama “deporter-in-chief” — under his administration in 2014, Immigration Customs and Enforcement deported around 70,000 unauthorized Mexican nationals, according to ICE data. This was a 16,000-person decrease from 2013, though, and a decreasing number of Mexicans have been immigrating to the United States since 2009, according to Pew Research Center reports.

But given Trump’s proven anti-immigrant policy goals — and campaign promises to build a “big, beautiful” wall and deport two to three million more “criminal” unauthorized immigrants — that number could begin to rise again.

The president’s anti-immigrant, build-the-wall rhetoric hasn’t appeared to sway immigration perceptions along the 110th meridian. But the ways in which residents of Ambos Nogales and Sweet Grass, Mont./Coutts, Alberta, which is more than 1,500 miles north of the southern border, tend to view immigration vastly differs.

Nogalenses — people from Nogales — tend to express more humane views toward unauthorized immigrants, while Sweet Grass and Coutts locals seem more likely to base their opinions on conservative media reports and political rhetoric in the likes of Donald Trump’s.

Geographically, this makes sense.

Around 5.8 million unauthorized Mexican immigrants (most of whom probably entered the country from Mexico via the southern border) resided in the U.S. in 2014, according to Pew Research Center estimates. Only around 100,000 unauthorized Canadian immigrants (most of whom probably entered from Canada via the northern border) lived here during the same year.

Furthermore, ICE deported 23,000 Canadian nationals from the United States in 2014, according to data from the agency’s website. In other words, three times as many Mexican nationals were deported compared to Canadians.

Residents who live along the significantly less-militarized border in Sweet Grass, Mont., and Coutts, Alberta, which are predominantly conservative, Trump-supporting communities (even in Canada) — people don’t think of immigration as an issue. It doesn’t directly affect residents on a daily or even monthly basis, Dan, owner of the Glocca Morra Motel in Sweet Grass, says.

“We don’t have any stuff like that stuff you guys have down [at the southern border],” Dan says.

Charles R. Hamilton, U.S. Border Patrol’s patrol agent in charge of the Sweet Grass sector, agrees with Dan. He says illegal immigration isn’t an issue Customs and Border Protection agents frequently encounter up north — a “low-threat, low-risk” area.

“[It’s] really not the primary issue. It’s not a problem that I say, ‘Oh, everyday we’re encountering illegals trying to cross or come across the border.’”

Daryl Anderson, superintendent of the Canadian Border Services Agency at the Coutts crossing, says over 95 percent of people crossing through Sweet Grass into Canada are compliant within CBSA’s regulations. When the agency does deal with that small percentage of people entering the country illegally, they deal more with “high-risk” people (i.e., terrorists and drug smugglers) than unauthorized immigrants.

Roger Orgus, a farmer who grows cereal grains in Sweet Grass, says he hardly ever deals with unauthorized immigrants on his land — an issue ranchers on the southern border deal with frequently. He says that he’s only encountered people attempting to cross the border illegally a few times in his 60 years living and farming in Sweet Grass.

“Every once in a while, someone will try to jump the line, but nothing major,” he says. “We’ve had a couple vehicles stolen by guys trying to get across after they got rejected up in Sweet Grass. It’s been four years ago, but there’s [usually] one or two a year.”

Tex and MJ Gilbertson, Coutts locals who spend their winters on the U.S.-Mexico border in Wellton, Arizona, 29 miles east of Yuma, say illegal immigration isn’t an issue in Coutts, to their knowledge.

“We don’t have a lot of people crossing,” MJ says. “Just dogs, cats, skunks.”

MJ Gilberstons talks about differences living part time on both the northern and southnern borders.

MJ says that while she and her husband have never witnessed immigrants attempting to cross the border illegally on the northern border, they’ve seen it plenty of times on the southern border. And they want Border Patrol agents to detain people attempting to cross illegally.

That’s a common theme with Coutts and Sweet Grass residents — they don’t really empathize with immigrants who cross into the U.S. or Canada without proper documentation.

MJ, Dan, Orgus and even Hamilton, a Border Patrol agent, all referred to unauthorized immigrants as “illegals,” which media giants such as the New York Times, the L.A. Times and the Associated Press (and even the Supreme Court) refrain from using, due to its implication that any immigrant who enters a country without proper documentation is a criminal.

The locals in Coutts and Sweet Grass tended to express this belief in their everyday language. They spoke of immigrants as sub-humans who shouldn’t have to be their problem.

That said, they still didn’t support further building up the wall on the southern (or northern) border.

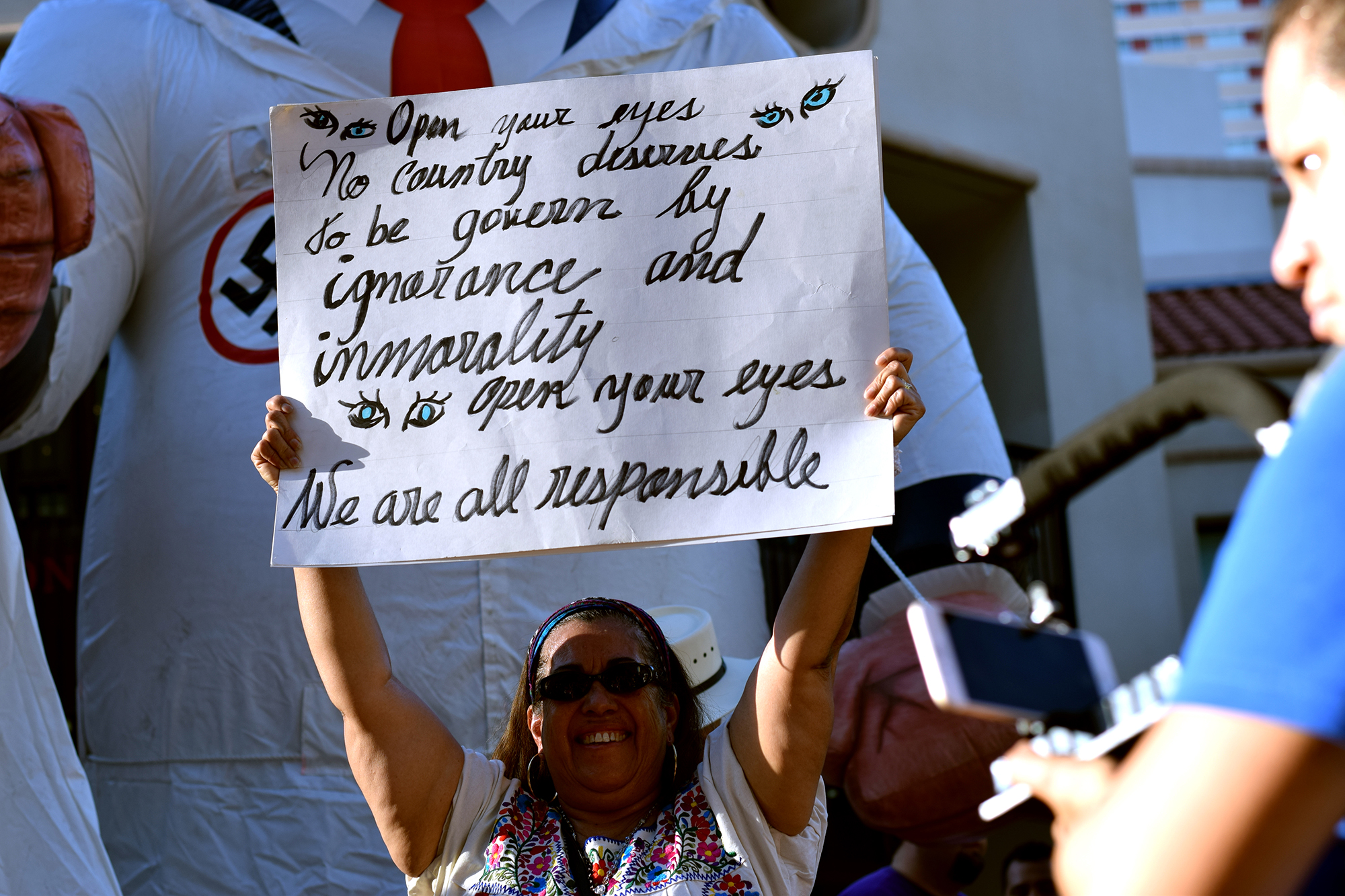

This anti-immigrant mindset, though less common, exists in Southern Arizona communities. Leyva says that while he’s “made many friends” throughout his time in Arizona, he’s also encountered plenty racists and xenophobes.

“[Arizonans] think I am a criminal … but I am not,” he says. “You know, you get to California, they are very welcoming. You get to New Mexico, they speak Spanish. You get to Washington state, they welcome you and say, ‘Teach me Spanish!’ But in Arizona, people’s mindset is more anti-immigrant. It was very hard.”

Leyva says it doesn’t help that the U.S.’s political climate becomes increasingly polarized in Trump’s isolationist America. He doesn’t think it’s fair that his hardworking character and devotion to the United States will be discounted solely because he is an undocumented immigrant.

“People should judge other people more [conduct]-wise, how they conduct themselves in their daily lives,” he says. “Not for race.”

Pablo Lechuga, a historian, elementary school teacher and local radio personality who lives in Nogales, Sonora, says in Spanish that most people immigrating illegally from Mexico really do just want to give their family to have a better life — to attain “the American Dream,” he says.

“There are millions of undocumented Mexicans over there, raising up the country along with Central Americans and Koreans, and a lot of respect,” he says. “They are human beings, and we all have rights.